By Rabbi Deborah Silver, Shir Chadash, New Orleans, Louisiana

By Rabbi Deborah Silver, Shir Chadash, New Orleans, Louisiana

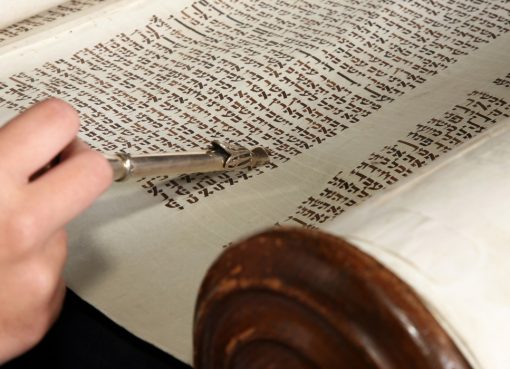

When we consider the centrality of Torah to our tradition—whether in the sense of the scroll in the Ark or our expanded use of the term to embrace the Tanakh and all of the literature of the teachers who came before us—it is interesting to consider the way we memorialize in community the time that Torah was given to us. In contrast to the Seder and the meals in the Sukkah, the Tikkun Leyl Shavuot, the tradition of studying throughout the night to prepare ourselves for receiving Torah anew in the morning, is curiously low on tangible symbols; and while we stand together the following morning to hear the narrative of revelation once again, the Torah scrolls will remain in the Ark waiting nearly half a year for us to dance with them and celebrate them. Today, some Jewish schools have taken up the custom of dressing children in white with floral garlands to commemorate the first fruits, the bikkurim, which is beautiful, but I believe that many of us have far less clear individual and communal connections to Shavuot.

What we do have is cheesecake.

It wasn’t until I made friends with a couple in California that I learned the way that cheesecake can imbue Shavuot with layers of delicious meaning. Let me introduce you to the concept of Cheesecakorama, a community celebration that takes place on the afternoon of the first day of the chag.

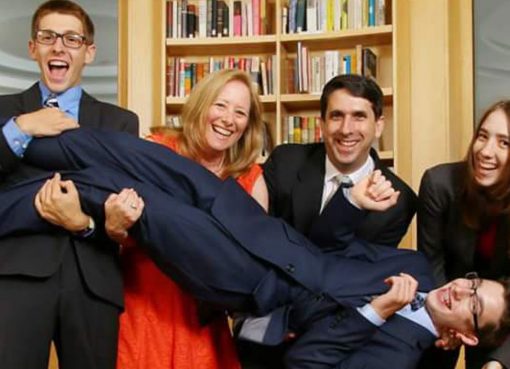

Cheesecakorama is the invention of Jo and Bill. It began when Jo discovered that Torah is often analogized to water and there’s a Moroccan tradition of coming home from synagogue, getting changed into casual clothing and having water fights. Jo and Bill’s garden boasts a large swimming pool, the weather in Southern California is reliably kind at that stage of the summer, and Jo, whose day job is as a rocket scientist (yes), loves to bake.

And so Cheesecakorama was born. The afternoon of the first day of Shavuot became the time for friends and family to gather at Jo and Bill’s, and for Jo, the counting of the Omer became the time to begin gathering recipes. There’s the classic Oreo cheesecake with the thick ganache topping and a cookie half-submerged in it to mark every slice; there’s the banoffee cheesecake with the smooth banana filling and the nutty caramel drizzle; and every year, there is some new twist, such as the matcha sesame cheesecake or the savory feta and tomato tart. While guests are invited to contribute (I used to bring my favorite chocolate mascarpone creation), it’s Jo’s cakes, in abundance, that make the kitchen table groan for mercy, that are the star of the show. Those who are still in a condition to take to the water after tasting do so, while other guests gather in little groups on the patio, on the sofa, around the kitchen table, mopping up stray crumbs and discovering new connections.

As those of us who were semi-comatose from having stayed up all night rendered ourselves more so, I would think about how—in the words of the Talmud—this, too, was Torah.

There are numerous Midrashim that analogize Torah to milk and honey. And the numerical value of the word for milk, halav, adds up to 40, the number of days that Moses spent receiving Torah on Mount Sinai. But, most of all, I would think of the verse from Psalm 34: Taste and see that the Lord is good.

Because this is a verse that doesn’t immediately make sense. What does taste have to do with seeing? Why do we need to taste in order to be able to perceive? I think, because taste is the human sense most closely allied to our instinctual selves. Think of how a small child will test new objects in its environment by mouthing them. We need to taste first, before we can begin to understand. The verse is teaching us that there is something about Torah that is easily and deliciously accessible—all we need do is reach for it and savor it. And furthermore, as my teacher Reb Mimi Feigelson likes to observe, what we eat does, in fact, become us. The cheesecake of today becomes the inspiration of tomorrow.

And we taste it together. Rashi teaches that the reason the Children of Israel are described in the singular rather than the plural when they stood at Sinai is that in some sense, they became one. There was something about the giving of Torah that brought them together as a single unit and began their journey toward community. I think, also, of the manna, the food of the Israelites for so many years in the desert, with its taste of wafers dipped in cream, and the relationships that would have formed over years as the Israelites went out to collect it morning after morning.

In our fractured and atomized lives, Shavuot reminds us that Torah nourishes us both singly and collectively—whether at the base of a mountain or around a pool on a sunny California afternoon. We just have to find a way back.

Dedicated with great love to the memory of my dear friend William Louis Friedman, gone too soon, who always used to complain the water was too warm.

About the Author

Rabbi Deborah Silver was ordained by the Ziegler School at the American Jewish University, Los Angeles in 2010. While there, she co-edited three volumes of the Ziegler Adult Learning Walking With… series with the school’s Dean, Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson, and also won the Whizin Prize for Jewish Ethics in 2009.

Comment here