Rabbi Kevin Hale, a trained sofer STaM scribe and member of the Rabbinical Assembly whose work focuses on evaluating and restoring Sifrei Torah, shares a special journey with his scribal mentor:

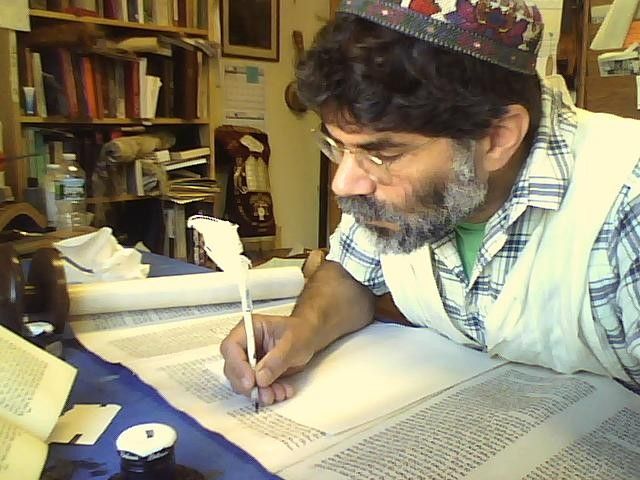

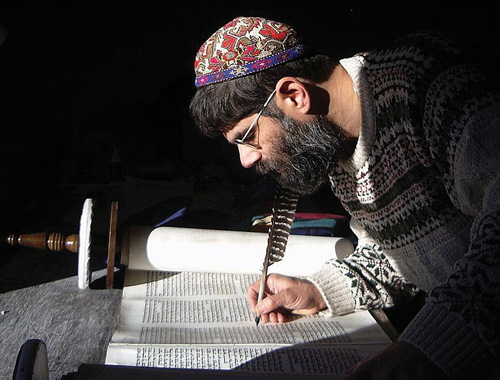

It is an exquisitely beautiful day in the middle of Elul in Western New England, and I am in my studio, hunkered down over an unusually tall 250-year-old Torah scroll with quill in hand and inkwell safely to one side, quietly calling out the name of each letter to be repaired as I touch pen to parchment. I gaze out the window of my studio where Roberts Meadow Brook feeds into the Mill River over the remains of dams, which 150 years ago powered the mills that made Leeds, Massachusetts, a world-renowned epicenter of the silk industry.

Along the banks stand oak and sugar maples suggesting this year the glorious New England foliage will reach its peak, along with leaf-peeping tourist traffic, right around Yom Kippur. I already stepped outside to sound the shofar, and must resist the urge to lay down my tools, cover the scroll with a tallit and step out of the scriptorium for a ramble up to the top of Roberts Hill. As much as my work as a sofer stam, a torah scribe, is a sacred calling, privilege and labor of love, it is also my parnassah, my living, and I know my teacher Rabbi Dr. Eric Ray worked on a deadline, and so did his teacher. But I would love to go outside, and as soon as I come upon an azkarah, a name of God, in need of rewriting, which requires immersion in mikveh, that will be my cue to run over to the beach on the partially dammed section of Roberts Meadow Brook for a dunk.

Within the four cubits of my scriptorium (so dubbed by my kids when they took Latin in middle school) is a holy clutter of parchment, feathers, tefillin parts, Torahs and megillah scrolls and tools, not to mention musical instrument parts and 78 Rpm records. Without venturing out, it is possible to ramble widely through Jewish time and geography. The scroll before me, replete with Kabbalistic embellishments, was written in Bohemia/Moravia before the American Revolution. It’s one of 1,564 scrolls saved from destruction during the Shoah and catalogued by workers of the Jewish Museum in Prague. Now belonging to the Westminster, London-based Memorial Scrolls Trust, #326 is on permanent loan to a synagogue in the Catskills. To my right is a very small Torah from a congregation in Modesto, California, written in Germany circa 1800 and most likely brought over during the Gold Rush, now placed on new and properly fitting eitzim, rollers. At the other end of my worktable is a nearly pristine Torah written in the mid-1930s in flawless Vilna-style script. Acquired from a now-disbanded USCJ congregation, it was barely used due to its size and weight. I am trimming the top and bottom margins to a manageable size and weight, to be revered and loved by a new congregation. On the wall beside the window hangs a framed panel of a reddish brown Torah, with folds between the columns speaking of active use in a Sephardic tik, cylindrical Torah case. The accompanying label is in my teacher’s impeccable handwriting:

Book of Genesis, Chapter 44-30 to 48:5

Circa early 17th cent. / Classic North African Sephardic script

Probably of Yemenite Origin

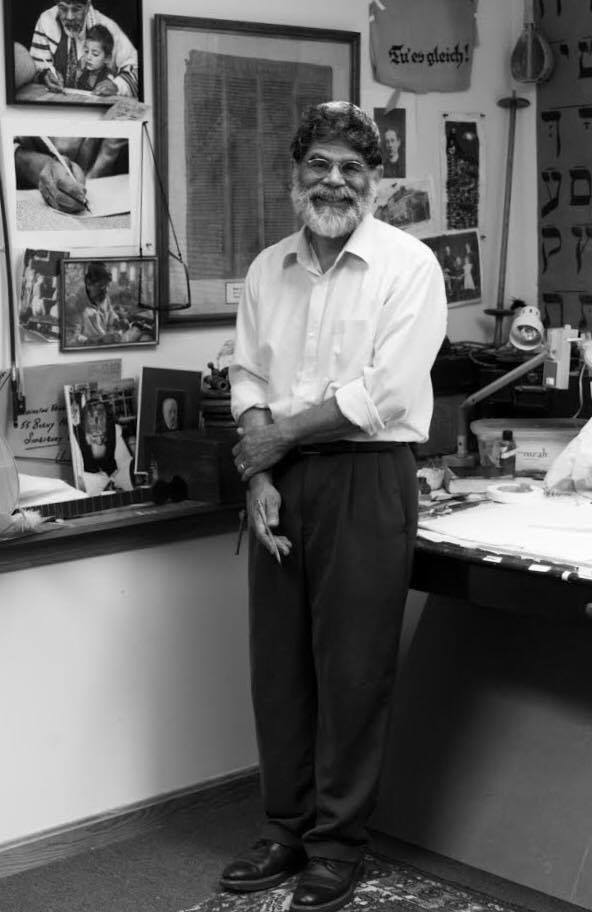

Each of these scrolls, being made kosher and usable, represent Jewish communities and Jewish historical eras that are out of reach or long gone. And yet, the century-old watercolor painting behind me, a gift from my antiquarian Judaica bookseller friend Ken Schoen, of a scribe (who looks very much like me when my beard was dark!) at work in his shop repairing a Torah with an assortment of scrolls and tools still more or less depicts my world today, or that of a scribe from almost any time and place in Jewish history.

My mentor, Dr. Eric Ray (1926-2004), trained me in all aspects of our sacred scribal tradition and I work fully conscious of the lineage. He was a full foot taller than me, regal and Lincoln-esque in stature with a refined British accent. I often imagine myself standing precariously on his shoulders. Already a gifted calligrapher, in 1947-1948, he was smuggled into Dachau in order to forge the papers that allowed stateless survivors to slip into Palestine despite the British White Paper. Eager to join the struggle for independence, he arrived in Tel Aviv by wading ashore from the smoldering ship Altalena. In the war of independence under the command of Yigal Yadin, the tall Englishman was given the nickname Aryeh va Chetzi (Aryeh and a half). After the ceasefire, he produced the first maps for the Israeli Navy. A working graphic artist and director for the University of Judaism’s School of Fine Arts, his study of archeology and ancient Hebrew scripts led him to become a master scribe who could identify 2,000 distinct Hebrew scripts. Dr. Ray was a foremost authority on the provenance of Hebrew script, the oldest identification of Torah scrolls without using carbon dating.

Travel was integral to my training as a sofer STaM. One of the blessings of my years of apprenticeship with Dr. Ray was the need to drive to Great Neck, Long Island, every month for two for three days at a time. With two very young children back at home, and Ruth generously holding down the fort along with her public health profession, it felt like an indulgent excursion to an exotic destination. I would spend days with Eric and his wife Lali, recently retired from her job as USCJ New York Area Director of Education, and evenings and mornings with my parents in the little house in Westbury where my 97-year-old father still lives. Lali and Eric regaled me with stories of their adventures in the context of his work as scribe and scholar-in-residence. Some of their adventures were local, such as the fabled 18th century Italian Torah restoration project for their own synagogue, Temple Israel of Great Neck. Dr. Ray’s book Sofer: The Story of a Torah Scroll was dedicated to his rabbi Mordecai Waxman in gratitude for his commissioning Dr. Ray for the project. They also visited communities such as B’nai Amoona in St. Louis, Mikve Israel-Emmanuel in Curacao, and Liberaal Joodse Gemeente den Haag in the Hague, where he identified a 13th century Torah scroll, without the help of carbon-14 dating. He believed this to be the oldest complete Torah housed in an ark in an active synagogue.

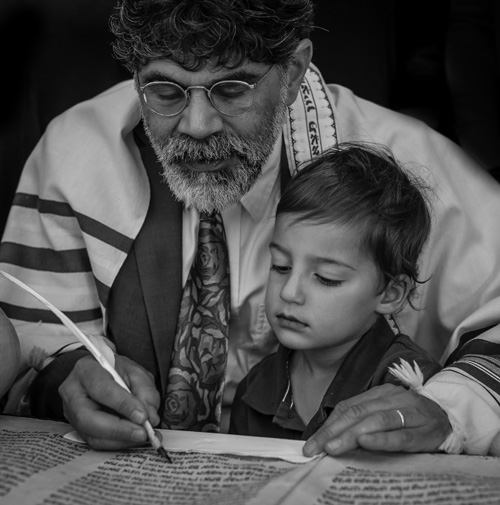

This work of evaluation, restoration, education and writing isn’t just done in my studio. There was a time when every small to medium town had a scribe, but outside of Israel, now the nearest scribe may be 500 miles away. A modern contemporary American scribe travels to educate as well as to conduct a ceremony of complete for new Torah or newly restored Torah. Scribal travel began early in my career, when Dr. Ray was invited to Pittsfield to evaluate 14 scrolls belonging to Congregation Knesset Israel and he asked me to meet him and help. It was my trial by roller, and I don’t believe I stepped outside for 10 hours. Eric narrated, describing each scroll as I took measurements and photos and, as designated “holy roller”, I physically rolled through the Torah—200 feet of parchment and about half a mile of handwritten sacred text. It would later turn into a lengthy report. All the while, Lali took notes as she watched over and chatted with my daughter Luna playing with toys beside her.

Over the years, I have visited communities large and small, and sometimes the scrolls themselves connect one community to another. In the case of the Memorial Scrolls Trust Torahs, a restoration is done on behalf of the destroyed Jewish community from which it was taken. It’s sometimes to the point of granting lifetime membership to each of the known names from that community, reciting their names at Yizkor. Just before the 75th anniversary of Kristalnacht, I began writing a mezuzah in the sole remaining synagogue in Oswiecim Poland (Auschwitz), continued writing the bulk of it in my studio and completed it the following Yom Ha Shoah in a siyyum at Ft. Hood, Texas, in a ceremony in which the last six letters were written on behalf of members of the Jewish community, military and civilian. The mezuzah returned from its travels to be gifted to the cafe next to the Auschwitz Jewish Center, and is touched daily by travelers from every corner of the world.

Dr. Ray was intimately involved with Torah until the end, a sought-after scholar-in-residence, who lacked the physical stamina to complete months-long restorations such as that of the Memorial Scrolls Trust Torah commissioned by Congregation Ahavas Achim of Savannah, Georgia, on their 100th anniversary in 2004. Dr. Ray had me detach the first 55 yeriot or panels, which I restored under his direction, while he focused on the final columns. He and Lali met me in Savannah for the siyyum weekend, the public re-completion of the last 18 letters when we would reattach the scroll. But prior to the ceremony on Sunday afternoon, an unknown number of letters would be written on behalf of additional donors before Shabbat, and so the last column was left unrestored. Somehow, at 2:00 a.m., stray letters throughout the column were not yet legible. Dr. Ray insisted on completing the work that night, and I insisted the same. In a compromise, we each took quill in hand. I crouched at the bottom edge of the table to restore letters on the lower half while my teacher reached above me to restore letters on the upper half. There is no other word that describes the scene as much as “spooning,” but neither of us had time to stop and regard the scene as it unfolded. Shortly before dawn, the work was complete, save for the 18 letters. I could not have done my part had he not trained me. My teacher and I were not so much working as one, but as partners in a unified scribal entity. It was as if the very source of Torah had arranged that his last student, who would inherit his practice and carry on his scribal lineage, would be of modest stature, so that he could fit within the arc of his reach.

I am back in my studio, and I dip my quill into ink as I reach a little uncomfortably for the top of the next column and for this, I have completely changed my position. By the second line, I spot a letter vav in the Tetragrammaton, so faded it might be mistaken for a yud. It’s time for go for a stroll to the river.

Learn more about the legacy of Dr. Eric Ray: www.drericray.org

Rabbi Hale is the subject of the forthcoming short documentary, “Commandment 613.” Click here to watch an excerpt.

Painting at top of page provided courtesy of Kenneth Schoen

Comment here