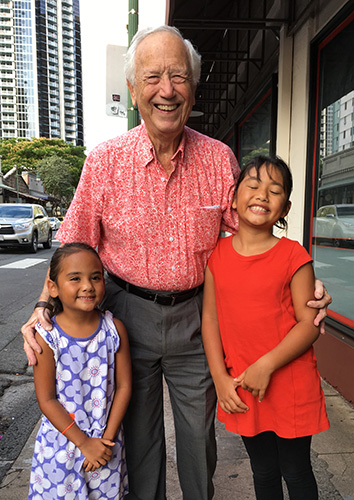

Alex Golub and Mathew Sgan of Congregation Sof Ma’arav share their journey of being Jewish in Hawaii, and how it led them to collaborate as research partners in writing a new book.

When most of us imagine centers of American Jewish life, we are more likely to think of Manhattan or Los Angeles than the middle of the Pacific Ocean. So for us, and the other members of our Conservative shul in Oahu, Hawaii, the question “What does it mean to be Jewish in Hawaii?” is something we hear almost every Shabbat. Although many of our fellow Jews in Hawaii have decided not to be involved in Judaism, we have made it our mission to emphasize the joys of Conservative Jewish observance and to continually invite others to join us to discover the answer to that very question.

Like many small Jewish communities, we work hard to maintain our culture and practice without the luxuries that come from living in places like Brooklyn or La Brea. Despite the challenges that presents, our small congregation of some 100 families has thrived for more than 40 years. How did this happen? When we set out as research partners to write a history of our congregation, we thought we would discover a story of resilience and community, which we did. Yet, along the way, we also discovered something more surprising: that many of the things we considered our greatest weaknesses were, in fact, our greatest strengths.

Jews have been living in Hawaii ever since the then-independent Kingdom of Hawaii became a source of fresh food and supplies to the California gold fields and to ships that stopped in its ports in the 19th century. Jews trickled in and played various roles as merchants and even as advisors to monarchs. But they failed to form a sense of community.

With U.S. Annexation in 1898 and WWI came military activities and its attendant population multiplier. The center of Jewish religious activity shifted to the military and those associated with it. In 1959, when the territory of Hawaii became an American state, a stronger Jewish community formed as Jews from the mainland moved to Honolulu, usually as part of their military service or to teach at the newly expanded University of Hawaii. With the founding of Reform Temple Emanu-El in Honolulu in 1960, the civilian population began to develop a real sense of a Jewish presence in Hawaii. In 1971, after feeling the need for more tradition-based Judaism than what was offered by the Reform temple, our Conservative congregation was established.

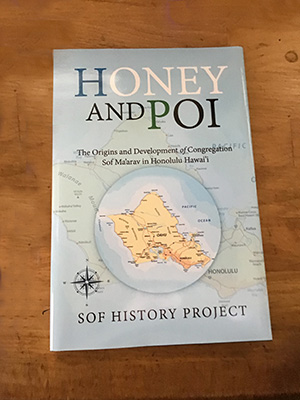

We originally decided to write a history of our congregation because we had noticed some of our founding members were getting a little grey in the temples and we wanted to make sure their stories would live on for future generations. As we interviewed members of our congregation, reviewed shul minutes and documents, and did library research, we learned stories that enabled us to construct a narrative highlighting the role our congregation played in so many Jewish lives in Hawaii. This narrative is described in our book, Honey and Poi: The Origins and Development of Congregation Sof Ma’arav in Honolulu, Hawai’i.

Our name, “Sof Ma‘arav” or “furthest west,” is a reference to the medieval poet Yehuda Halevi’s poem lamenting that he was in Spain, while his heart lay in Jerusalem. We knew many of our members had moved to Hawaii from the mainland. Therefore, we expected our story might be one of survival against the odds and nostalgia for the “old world” of the East Coast. But instead, we often found self-reliance was not a threat, but an opportunity that enriched us.

Sof Ma‘arav is a lay-led shul with no rabbi or cantor (although rabbis and cantors have at times been members of our congregation). Our members volunteer every week to leyn Torah, study Talmud and the parashat of the week, give a drash, lead services, educate adults and children and provide for the oneg. A group can’t arrange something that demanding with just a few people; we’ve had to develop, to use a sports term, a “deep bench.”

We have found that when we are forced to rely on ourselves like this, people rise to the challenge and deepen their knowledge of liturgy, Jewish history, Israel, and what it means to be Jewish. The result has been a community where people have taken responsibility for their learning. We have a more educated, interactive, and capable congregation as a result. We like to think of ourselves as having the benefits of a larger synagogue and the warmth of a close family.

For years, Sof Ma‘arav has rented space from the Unitarian Church of Honolulu, which meets in a converted mansion in the valley of Nu‘uanu. This has given us a chance to form a strong interdenominational partnership with another faith-based community. Another not-to-be overlooked benefit of being in Hawaii is that our sanctuary was originally designed to be a lānai (verandah). We can open and close the floor to ceiling sliding glass doors if the rain starts to come in or the rustling of the ferns and palm trees gets too loud on a lovely day in paradise.

In the course of our research, we also noticed some other, more subtle patterns in our history. One of the major concerns our history revealed was about replacement. Like many people in Hawaii, we find that our children move away to the mainland for school and work and often don’t return. But, at the same time, whenever someone moves away, someone else moves in. We’ve been fortunate—or perhaps someone is looking out for us—to have new members move to Hawaii and join our shul just when we seem to need new vitality the most.

Ultimately, researching and writing this book was a journey that really made us proud of our small community. We feel that Sof Ma‘arav has learned lessons that have not only helped us flourish, but may be relevant for other congregations in other cities. In the long run, it may be that the best way to create an authentic and dynamic Judaism is not to bring Brooklyn to Honolulu, but Honolulu to Brooklyn!

Comment here